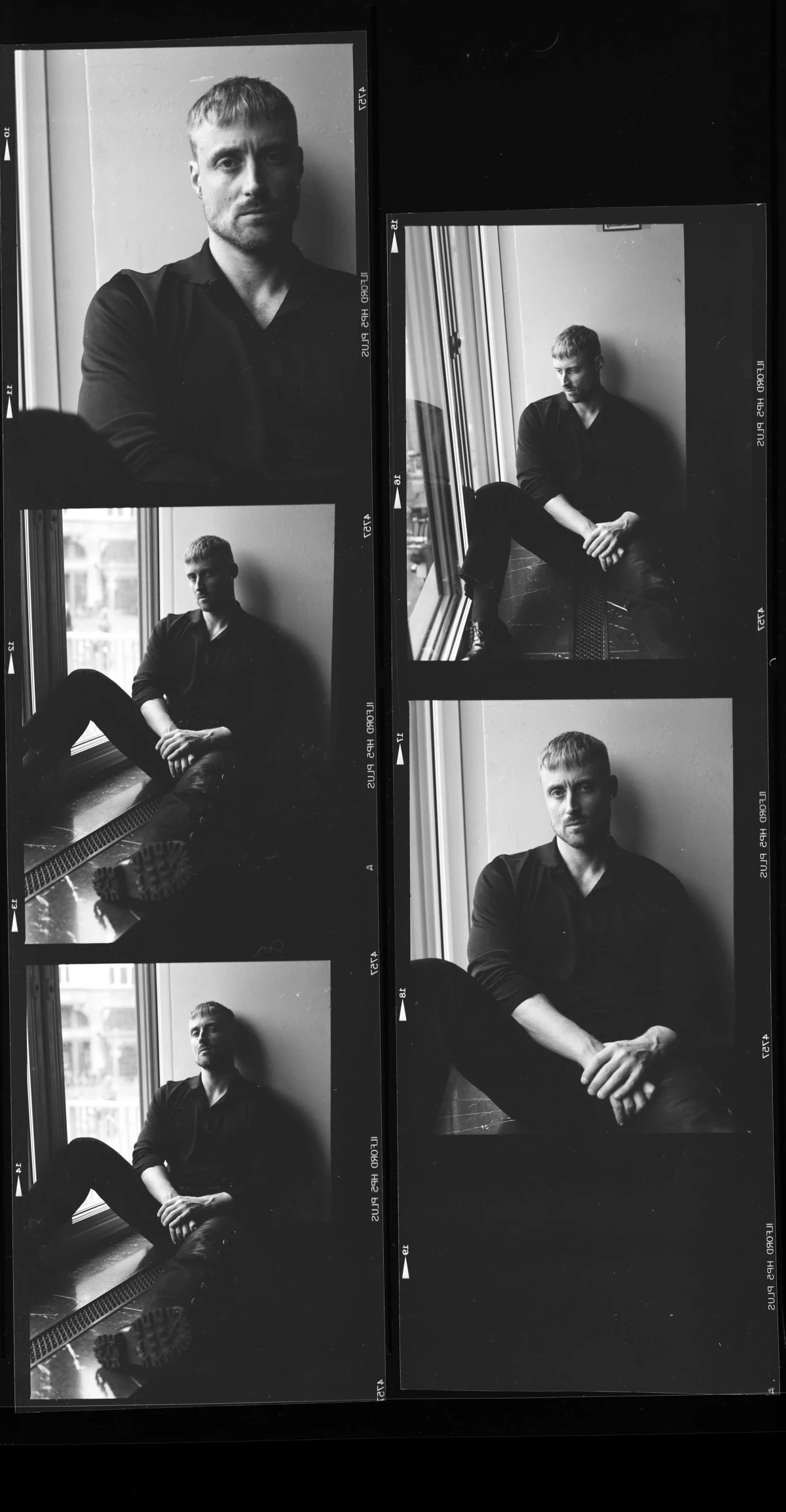

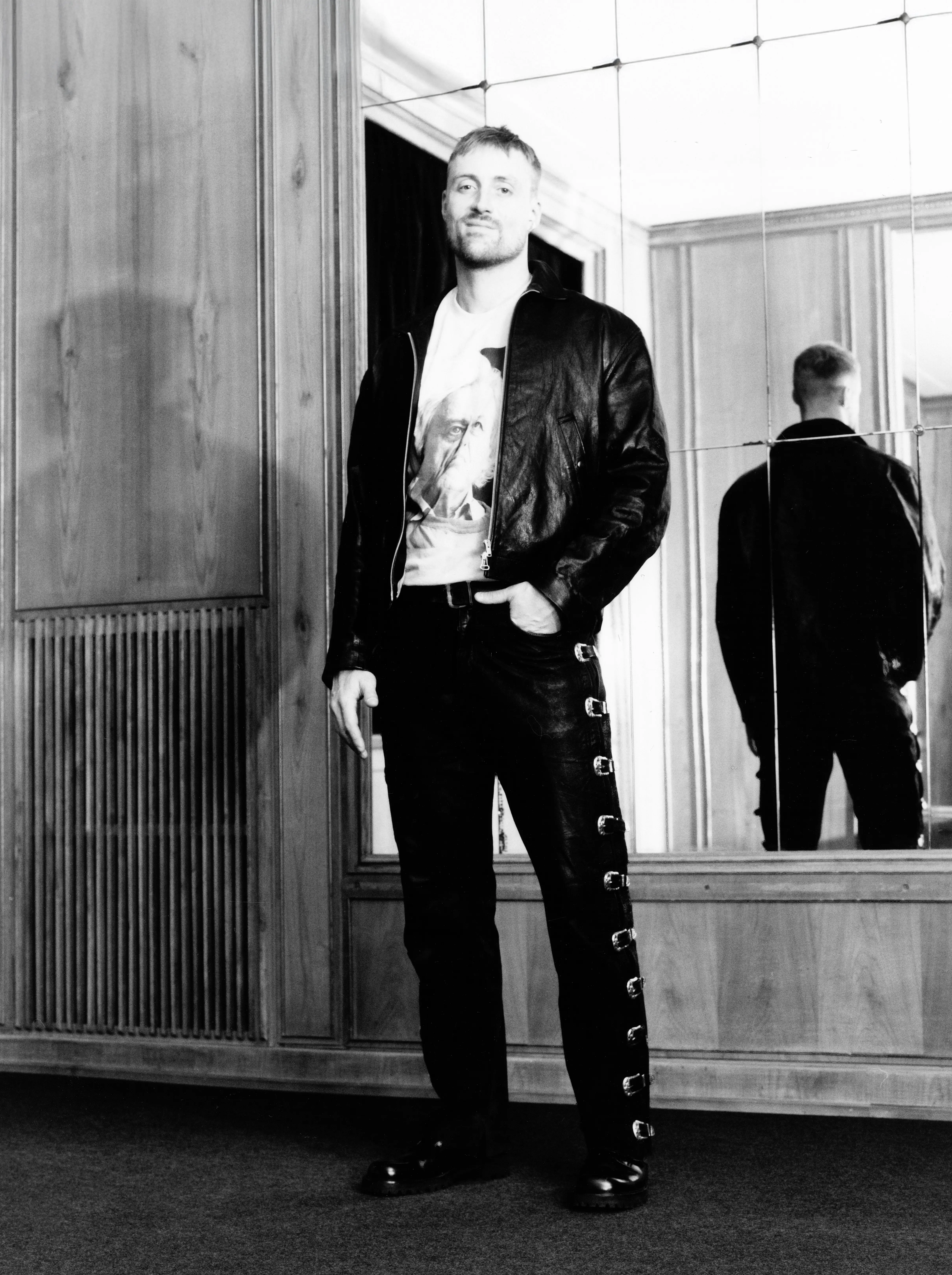

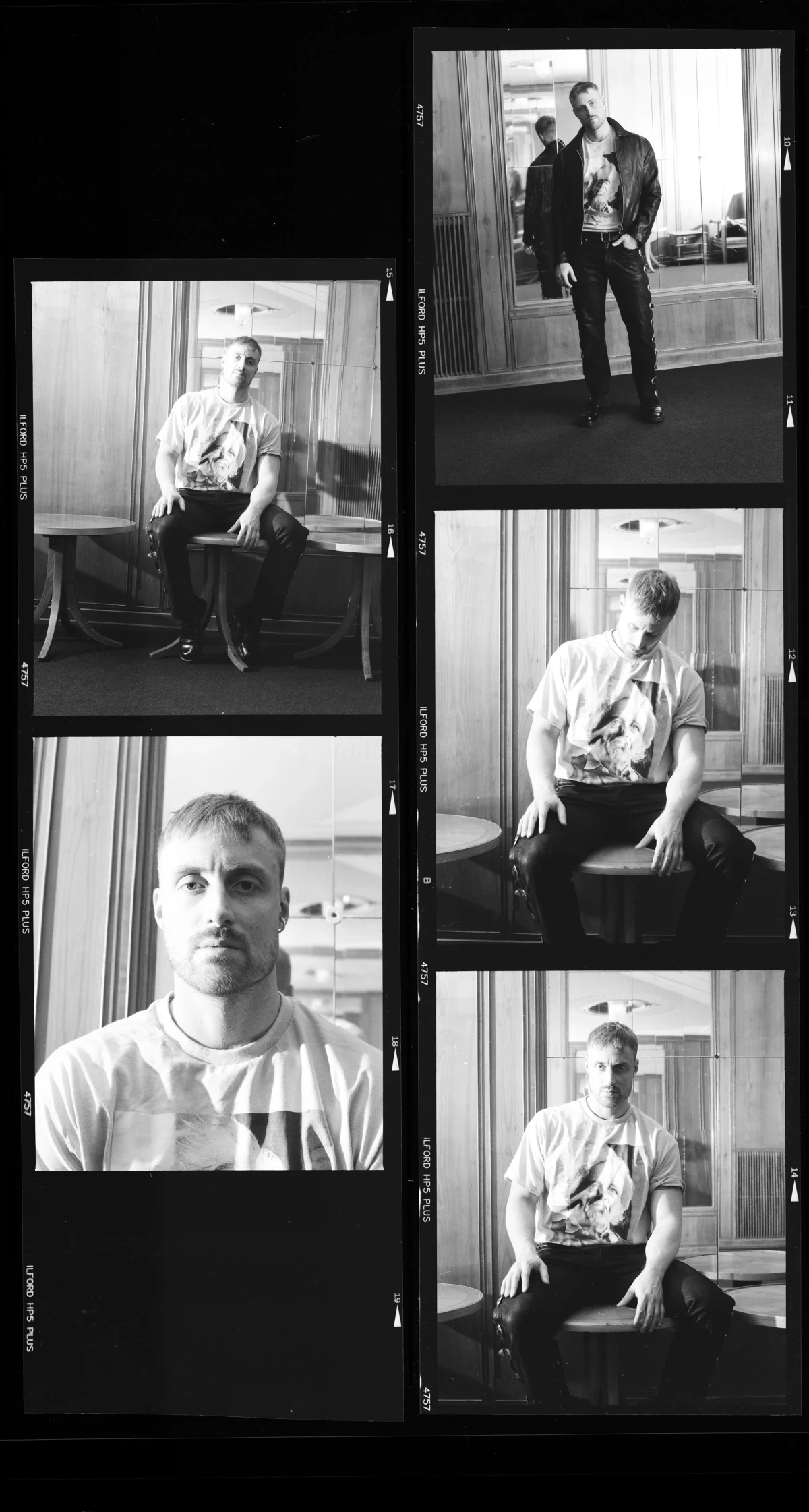

Billy Bultheel. The Belgian composer and multidisciplinary artist paints musical landscapes as diverse and intricate as his catalogue of projects. Rooted in a profound appreciation for both medieval musical traditions and contemporary experimentation, his work spans industrial-inspired soundscapes to delicate compositions that blur the boundaries between performance art and music. Known for his collaborations with various artists, including his longstanding work with visionary artist Anne Imhof, Bultheel has composed and performed the music for several of her acclaimed works.

Whether crafting soundscapes for works like “Unter” in a postmodern swimming hall as part of a collaboration between “DISAPPEARING BERLIN” and “RADIALSYSTEM” or performing the premiere of “The Thief's Journal” in the turbine hall of the former East Berlin power plant “Kraftwerk”, Bultheel treats space as an integral element in shaping sound.

On a particularly cold and cloudy autumn day, I met Billy Bultheel in his Berlin studio, tucked inside one of the many former industrial buildings the city is known for. As we climbed the stairwell, the sound of a saw machine echoed from outside, growing quieter the higher we went until it faded behind the large steel door leading to his space. Over warm tea, we delved into Bultheel’s journey, from his early days to his current ventures and creative process, that redefines the role of sound, space, and storytelling in modern composition.

Betty: How are you? You've been away.

BB: I'm good. I was in the States for a bit, but I'm back now. It’s been a lot of travelling and it’s nice to be back here.

Betty: You have something coming up at “Volksbühne”. Tell me about your contribution to “EEXXOO”.

BB: I created a piece called “The Short History of Decay”. It's part of the “EEXXOO”- series, which Marlene Engels is curating at the “Volksbühne”.

Betty: When we talked before, you hinted at creating a new instrument for this piece and exploring a new approach. Could you tell me more about that?

BB: I'm currently collaborating with ceramicists, as well as glassblowers, to make resonators modelled after mysterious acoustic vases found in medieval churches, all around Europe and Russia. They are found built into the walls of these churches, with their openings protruding out into the space and with large valves or corks that can be opened and closed to alter the acoustics and resonances of the surrounding space.

Betty: That’s such an intriguing concept. The architecture itself being part of the soundscape. How would they have worked exactly?

BB: They function like a filter or an equalizer, passively shaping the acoustics of each space. Every room has its own resonant frequencies, where certain tones resonate more strongly than others. These large resonators allow us to emphasize specific frequencies over others. For example, if a composition is centered around a particular note, like D or G, we can open the resonators that naturally harmonize with that frequency and its overtones. You don't need to interact with them directly; they simply enhance the sound as air passes through.

Betty: And how did you modernize these medieval resonators for your project?

BB: I'm essentially reimagining them using glass and ceramics. I've built speakers into these vessels, so we can play music directly through them, allowing the sound to filter through and resonate. This setup lets us use either recorded music or amplify live instruments, to sound within the natural resonance of the vessels.

Betty: I can’t wait to experience this live. Let’s jump from your most recent musical journey to the start of it all. What impacted you the most in your musical studies?

BB: I started playing music at a young age, but a major shift came when I moved to the Netherlands when I was 18. I enrolled in a master’s program called Sonology, which focuses on electronic music. It was influenced by big 20th-century composers like Xenakis, Koenig, and Stockhausen. Being in a school rooted in their legacy was very impactful. I was already interested in electronic music. My parents listened to experimental music, so I’d grown up with it. But studying there introduced me to medieval music, especially the Franco-Flemish traditions. It made me want to bring concepts like polyphony and abstraction from medieval compositions into electronic music.

Betty: How did these influences begin shaping your vision to eventually merge your composition skills with the art of performance?

BB: I became fascinated by how the context in which we listen to music shapes our experience of it. At Synology, music was typically presented in dark spaces, where the focus was on the abstract sound design and cerebral composition. But I wanted to make it more theatrical. Exploring how listening changes when we bind it to a more emotive environment, existing of people, objects, words and thoughts. Each environment or relationship creates a new dimension for the music. I started looking for ways to incorporate these landscapes into my work, to allow each space to shape the music diferently. Performance spaces became almost like an instrument themselves, adding depth and transforming the overall experience of the music.

Betty: It’s unfortunate that music can feel like it has an entry barrier. At least, that’s what it feels like to me. The mathematical side, especially with composers such as Karl-Heinz Stockhausen, who you mentioned earlier and whose work often reflects mathematical precision and organization, can be intimidating. Does that side of music appeal to you? Would you say you are a bit of a maths nerd, or do you solely use mathematics as a tool?

BB: I think in a way, yes. Many early 20th-century composers were deeply fascinated by mathematics, numbers, and patterns. For them, it was almost a reaction against the wave of romanticism that came before. I’m definitely interested in numbers too. That’s actually one reason why medieval music fascinates me. It also has this kind of mathematical approach, but in a way, it still leaves room for a lot of emotional depth and evocative imagery. I think what drew me in was this balance of abstract numerical structure and a direct connection to human emotion.

Betty: When it comes to compositional practice, it feels like there's often a divide. Some people describe it as a kind of spiritual experience, like inspiration striking from above, while others lean on the mathematical, scientific side and use numbers and harmonies that fit in a precise way. How does this balance play out in your work? Or does one side outweigh the other?

BB: I think there’s actually a third approach that often gets overlooked. It's about simply being a musician. Having that lifelong experience with an instrument, building a relationship with it, and improvising. When you play, these approaches blend. On one side, inspiration flows through you, and the sound becomes an extension of your expression. On the other, your body memory holds those musical, even mathematical, patterns, and it all just makes sense. Composing, for me, is like a dialogue with both instinct and inspiration. It’s a very generative space.

Betty: Like in the field of physics, where a theory or observation often starts with a simple assumption or impulse, and math steps in as a way to prove or explain a pattern that’s already there.

BB: Exactly. For me, composing isn’t about following a set theory, it’s more like creating an experiment. I bring together diferent elements to form an environment, a sort of musical “physics,” where things can emerge organically. Through exploration and interaction with musicians, everything starts to make sense within that space. For example, the way we’re setting up the stage at “Volksbühne” creates a space where sound will naturally respond to its surroundings. I enjoy creating these complex, experimental environments where music is born from the friction and interplay of all the active elements.

Betty: That must be quite intimidating even. You’re working with so many diferent elements. The sound, the space, even the audience. They all blend, and the outcome isn’t always predictable because of all the moving factors. A potential for chaos.

BB: Absolutely. It’s full of challenges, or let’s say, “problems” seeking elegant solutions.

Betty: Earlier, you mentioned the role of inspiration in your compositions. On your album “Two Cycles”, many of the track titles reference literary works. Were you reading and engaging with these texts while creating the music? Did the emotions or themes from them directly influence the songs?

BB: Actually, I rarely have a title ready when I write a song. It’s usually just music until there’s a moment when it feels right to name it. Often, I’ll start with a sketch name, something random, like “Two Tuba Thursday Song”. But with “Two Cycles”, the naming process was more intentional. This album was a collection of many previous projects, all of which are somehow congregated into one work, almost like a retrospective or a library. I started linking certain pieces to books that held meaning to me, not necessarily connected to the music, but significant on their own. In the end, it became a sort of ode to these texts that have accompanied me over the years, tying everything together.

Betty: In “Non-Cochlear Sonic Arts”, which you once referenced as an influence, Seth Kim Cohen discusses 'non-cochlear' music, music that isn’t confined to sound alone but works conceptually and even physically. What does this mean to you?

BB: He’s really interested in music as something sculptural or something that can be shaped and formed. I feel like my performances incorporate that element in by adding a certain materiality to the music. They also give the musician a presence, a materiality of their own. In many concerts, musicians can become invisible, dressed in black, with the focus only on how they play the music. In my pieces, though, they become characters moving within a landscape, actively interacting with the space and the music itself. So, there’s a physical approach to musicianship in my work.

Betty: Cohen also references Duchamp, whose work sparked discussions on the philosophy of art itself and transcended thereby the medium. Could your references of literary works be seen or interpreted as something similar? Another way of making the music physical and transcending the term music itself?

BB: With the connection between songs and books, it wasn’t so much about adding physicality. It was more about building a fragmented narrative into the music. For me, creativity isn’t about making statements or following strict theories which I then propose to an audience. It’s more about forming a network of diferent points of inspiration, diferent gestures, so the connections between them can generate something on their own. It’s really about creating something where the whole is more than just the sum of its parts.

Betty: I think Tyler, the Creator once mentioned something similar in an interview once. He calls them “reference points” and how he thinks every artist has them. But he believes that the most groundbreaking artists are those with the most diverse reference points, ones that are so far apart in medium or genre. Mixing these vastly diferent ideas is what makes someone’s art unique.

BB: Yes. It’s when, say, a song, a band, or an object just fits together in my mind, like pieces of a puzzle. I might not always know why, but when I put them side by side, something clicks. That’s where the experiment part of it comes in.

Betty: Let’s come to another inspiration of yours: György Ligeti, one of the biggest names of avant-garde composition. He used car honks in some of his compositions and describes his approach to composing as taking “scraps out of the trash of music'”, musical quotes, he calls them, which he twists and reinterprets. Do you also work with unconventional scraps or quotes like this? I noticed some table firecrackers over there on your recording table.

BB: I mean, I’ve worked with... what are they called... “Firecrackers...”?

Betty: Knallerbsen! I guess “cracker peas”.

BB: Right, cracker peas. I actually made a piece for solo percussion using them, where the performer plays and throws them on the floor as part of the score. I guess it can connect back to that mid-20th-century fascination with the industrial, or even earlier, with people like Varese and “musique concrète” composers, that brought in all kinds of machine sounds. For me, though, it had a more theatrical quality, and probably more to do with an admiration for industrial music and metal, especially from the 90s. So, it’s less about integrating scraps into an orchestral setting and more about referencing subcultures and the political undertones they carry.

There is a stack of books on the table before us, one of which especially grabs our attention.

Betty: “The Snows of Venice” by Alexander Kluge and Ben Lerner. It’s also the title of one of your compositions on “Snow Cycle”.

BB: It's such a gorgeous book, I love it. I picked it up at a conference somewhere, and it’s been a favourite ever since. Alexander Kluge is an artist I admire deeply; he’s worked extensively in theatre and film. Ben Lerner, on the other hand, is an American poet. This book is a collection of their essays, dialogues, and poetry, and it’s exactly the kind of work I love. It ties back to what we talked about earlier. This referential way of thinking, where ideas and moments come together, almost fragmented, to create a poetic and interconnected world.

We start to flick through the pages

BB: There is one particular poem in here, that somehow connected the book to that specific composition for me.

Billy begins to read reading the poem out loud

Music strikes an area, not a point (by Ben Lerner)

*It goes up one leg and stops the heart

This is what happened in central Europe

(The hooves of sleepers on the grass

Create potential pathways for the melody)

Then travels down the other in an instant

Bodies smoke among blue flowers The timbre structures split or scar

Producing the illusion of agency (Schoenberg himself detested the term)

“Never wake a collective subject” Voltage fluctuates across the scalp

Like a tornado touching down The dream selects its sleeper*

Betty: Wow, that’s very vivid and layered. I think I need to let that sit for a moment.

BB: Yeah, right? It just has this sense of music being embedded within a landscape. The idea of agency or producing the illusion of agency. I don’t know ... it felt like a lot of those terms really connected with my music.

Betty: Destruction is also a central theme in the rest of the book. It’s a concept that often unsettles us due to its deeply ingrained negative connotations. Yet, destruction can also be transformative, paving the way for renewal and creation. The title of your new work, “A Short History of Decay”, appears to engage with this exact theme. What is your relationship to destruction, both as a concept and as a creative force?

BB: There are so many ways to think about destruction in music. In a way, music is always destroying itself. It exists only in the moment you’re experiencing it. When you’re really engaged, especially for me when I’m playing or improvising, there’s this moment where the music takes over your body, and it becomes the only thing that exists. And then, it’s gone. It only remains as a memory, or maybe in a repetition of itself. That ephemerality feels deeply tied to destruction. On the other hand, I’m also very drawn to destructive processes in music, like algorithms or methods that take a melody or sound and break it down. Fragmentation, distortion, or similar processes that "damage" the original sound create something entirely new.

Betty: I love the image of snow melting and nourishing the next cycle as a metaphor the book title hints at. Destruction as an end to one thing but at the same time a necessary starting point for a new emergence. Do you see this pattern emerging and do you apply this to your own path?

BB: I feel like this year has marked the start of a new cycle for me. “Two Cycles” was, in a way, a goodbye album, a culmination of the past seven or eight years of my career. I had never released a solo album before, but I’d worked on so many projects, and this was a chance to bring them all together into one cohesive work, almost as a final statement. “The Thieves Journal”, a performance piece that incorporated the music from “Two Cycles”, had its last showing in Lisbon in September, closing that chapter.

Betty: Do you feel a new cycle emerging?

BB: Yes, one where I want to move beyond writing music just for the sake of it or focusing on abstract, clever ideas. Instead, I want to create pieces that feel deeply personal and explore topics close to me. For example, “Workers in Song”, the project with James Richard that I’ve been performing over the past year, feels like the first piece in this new cycle. It’s rooted in a very personal moment in my life: When I struggled with my sexuality and came out. It’s a work that touches on darkness and joy, life and death. All these emotions that have shaped who I’ve become.

That project felt like having a conversation with those feelings, and James was such an incredible collaborator in helping me bring that work to life. “Short History of Decay” is the second work in this new cycle. It feels more connected to a contemporary sense of sadness or hopelessness tied to the current political situation but also to the idea of new energy emerging from destruction, as you mentioned earlier.

It leans more toward program music or theatre, not just a concert, but something that fully embraces a specific theme.

Betty: Some outlooks for the end: I feel like your music would lend itself perfectly as a soundtrack for a movie. Would you be interested in that?

BB: Oh, absolutely. I’m already working on it; I scored a film in April and have another coming up in January. I love cinema and collaborating with people, and working in film is something I’m excited to do more of.

Betty: Would you have a preferred movie genre for your music?

BB: I feel like I should say indie cinema, but honestly, I’d love to create a science fiction soundtrack, that would be really cool. Also, it would be interesting to work with a director that is interested in using the sound system of a cinema space as an instrument. Cinema sound systems are incredibly complex, allowing for some amazing possibilities. Watching a film is already a sonic experience but emphasizing that aspect would be very exciting.

Betty: Is there something else you’d like to experiment with?

BB: Aside from what I’m working on now, I’d love to write something for a choir and work closely with vocalists. I also adore instruments like bagpipes, the oboe or clarinet. Writing a piece for twelve clarinets would be incredible. Or a big challenge might be composing for an orchestra.

Betty: I’m looking forward to listening to an orchestral piece by Billy Bultheel. And in the meantime, we’ll be going to “Volksbühne” in December.

BB: Something else to look forward to is my band, 33, a project with Alexander Iezzi, Cem Dajjal and Ivan Cheng. It leans toward industrial, experimental, and a bit of pop music. We will perform at the CTM festival in January here in Berlin.

Betty: Thank you for your time, Billy.

BB: Thank you.